Note

Go to the end to download the full example code.

Estimate a GEV on the Fremantle sea-levels data¶

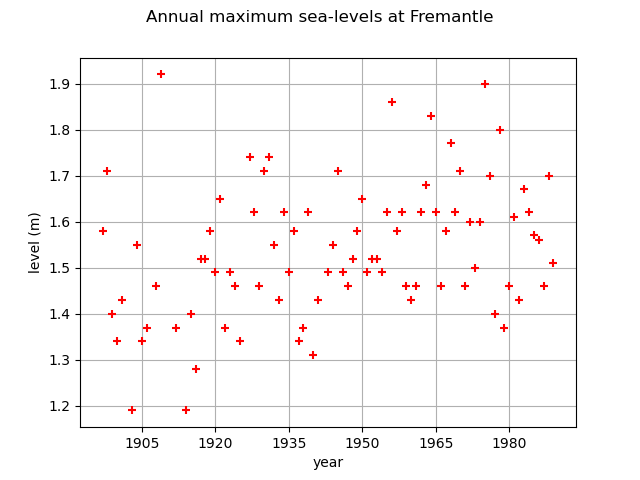

In this example, we illustrate various techniques of extreme value modeling applied to the annual maximum sea-levels recorded at Fremantle, near Perth, western Australia, over the period 1897-1989. Readers should refer to [coles2001] to get more details.

We illustrate techniques to:

estimate a stationary and a non stationary GEV depending on time or on the covariates (time, SOI),

estimate a return level,

using:

the log-likelihood function,

the profile log-likelihood function.

We also illustrate the modelling with covariates.

First, we load the Fremantle dataset of the annual maximum sea-levels. We start by looking at them through time. The data also contain the annual mean value of the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), which is a proxy for meteorological volatility due to effects such as El Nino.

import openturns as ot

import openturns.viewer as otv

from openturns.usecases import coles

data = coles.Coles().fremantle

print(data[:5])

graph = ot.Graph(

"Annual maximum sea-levels at Fremantle", "year", "level (m)", True, ""

)

cloud = ot.Cloud(data[:, :2])

cloud.setColor("red")

graph.add(cloud)

graph.setIntegerXTick(True)

view = otv.View(graph)

[ Year SeaLevel SOI ]

0 : [ 1897 1.58 -0.67 ]

1 : [ 1898 1.71 0.57 ]

2 : [ 1899 1.4 0.16 ]

3 : [ 1900 1.34 -0.65 ]

4 : [ 1901 1.43 0.06 ]

We select the sea-levels column.

sample = data[:, 1]

Stationary GEV modeling via the log-likelihood function

We first assume that the dependence through time is negligible, so we first model the data as independent observations over the observation period. We estimate the parameters of the GEV distribution by maximizing the log-likelihood of the data.

factory = ot.GeneralizedExtremeValueFactory()

result_LL = factory.buildMethodOfLikelihoodMaximizationEstimator(sample)

We get the fitted GEV and its parameters .

fitted_GEV = result_LL.getDistribution()

desc = fitted_GEV.getParameterDescription()

param = fitted_GEV.getParameter()

print(", ".join([f"{p}: {value:.3f}" for p, value in zip(desc, param)]))

mu: 1.482, sigma: 0.141, xi: -0.217

We get the asymptotic distribution of the estimator .

In that case, the asymptotic distribution is normal.

parameterEstimate = result_LL.getParameterDistribution()

print("Asymptotic distribution of the estimator : ")

print(parameterEstimate)

Asymptotic distribution of the estimator :

Normal(mu = [1.48231,0.141241,-0.217052], sigma = [0.0176728,0.0105976,0.0776361], R = [[ 1 0.15748 -0.482101 ]

[ 0.15748 1 -0.411378 ]

[ -0.482101 -0.411378 1 ]])

We get the covariance matrix and the standard deviation of .

print("Cov matrix = \n", parameterEstimate.getCovariance())

print("Standard dev = ", parameterEstimate.getStandardDeviation())

Cov matrix =

[[ 0.000312329 2.94943e-05 -0.000661467 ]

[ 2.94943e-05 0.000112309 -0.000338463 ]

[ -0.000661467 -0.000338463 0.00602736 ]]

Standard dev = [0.0176728,0.0105976,0.0776361]

We get the marginal confidence intervals of order 0.95.

order = 0.95

for i in range(3):

ci = parameterEstimate.getMarginal(i).computeBilateralConfidenceInterval(order)

print(desc[i] + ":", ci)

mu: [1.44767, 1.51694]

sigma: [0.12047, 0.162012]

xi: [-0.369216, -0.0648881]

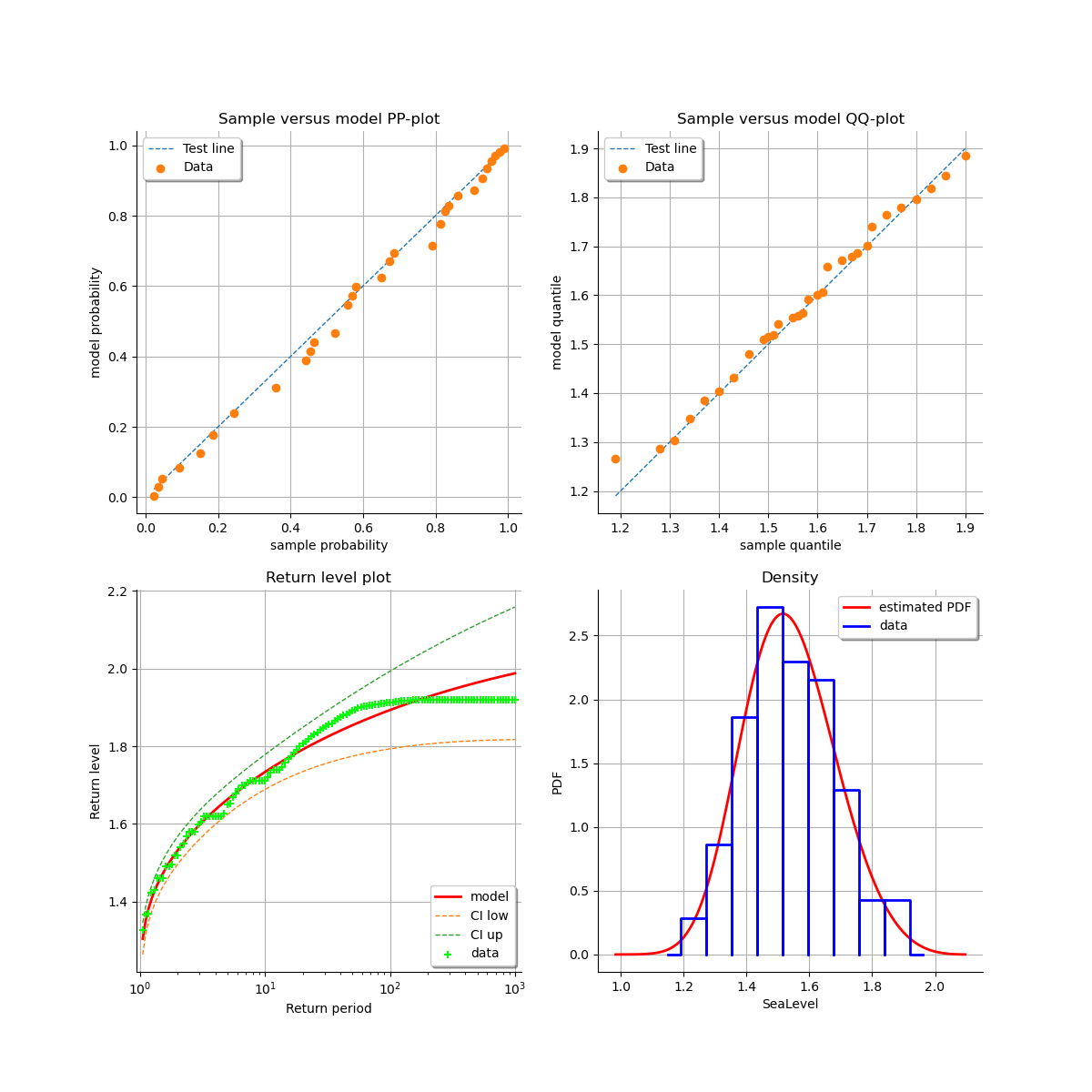

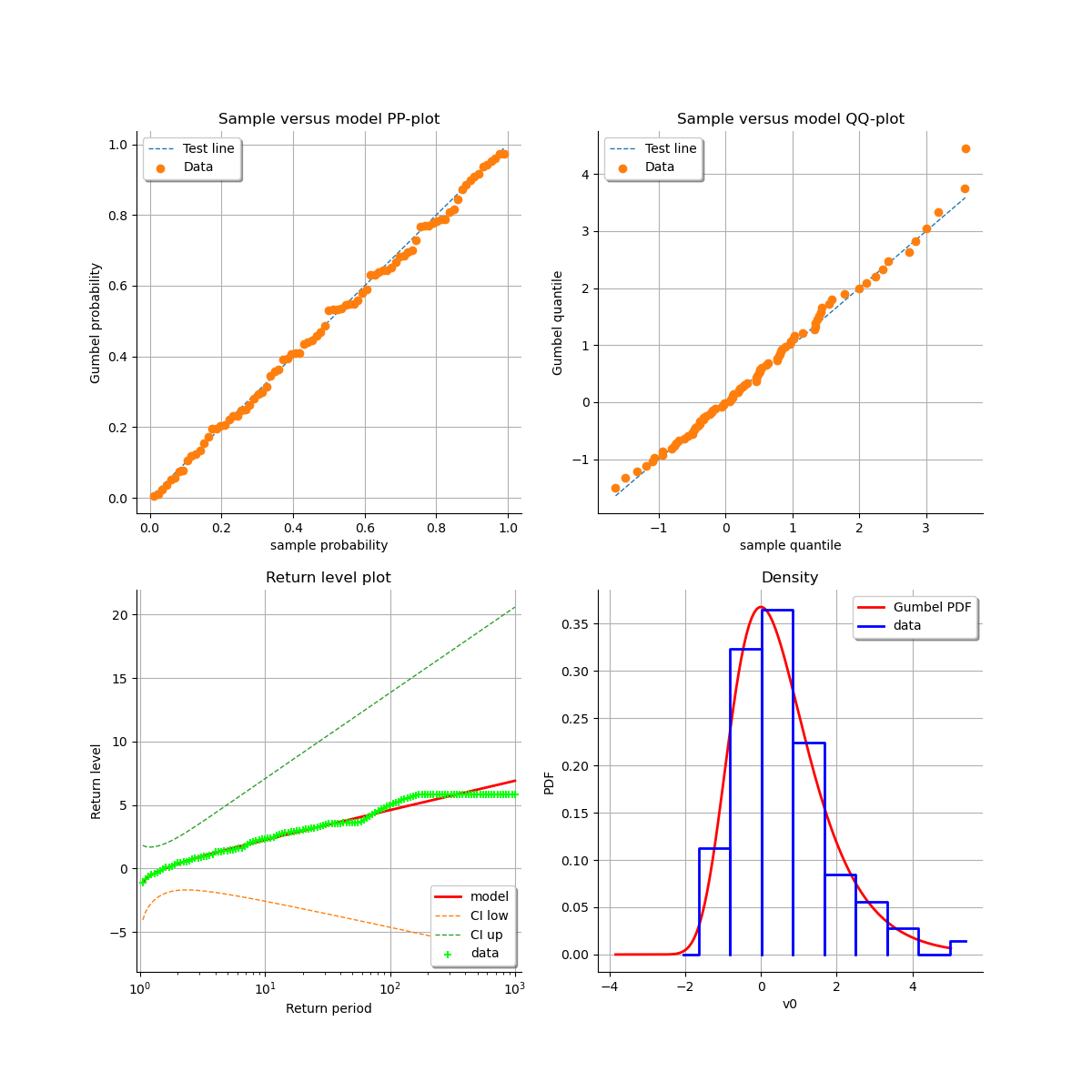

At last, we can validate the inference result thanks the 4 usual diagnostic plots:

the probability-probability pot,

the quantile-quantile pot,

the return level plot,

the empirical distribution function.

validation = ot.GeneralizedExtremeValueValidation(result_LL, sample)

graph = validation.drawDiagnosticPlot()

view = otv.View(graph)

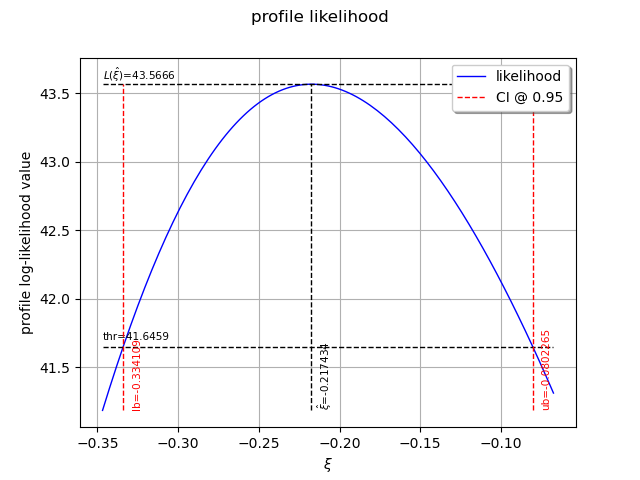

Stationary GEV modeling via the profile log-likelihood function

Now, we use the profile log-likehood function rather than log-likehood function to estimate the parameters of the GEV.

result_PLL = factory.buildMethodOfXiProfileLikelihoodEstimator(sample)

The following graph allows one to get the profile log-likelihood plot.

It also indicates the optimal value of , the maximum profile log-likelihood and

the confidence interval for

of order 0.95 (which is the default value).

order = 0.95

result_PLL.setConfidenceLevel(order)

view = otv.View(result_PLL.drawProfileLikelihoodFunction())

We can get the numerical values of the confidence interval: it appears to be a bit smaller than the interval obtained with the log-likelihood function. Note that if the order requested is too high, the confidence interval might not be calculated because one of its bound is out of the definition domain of the log-likelihood function.

try:

print("Confidence interval for xi = ", result_PLL.getParameterConfidenceInterval())

except Exception as ex:

print(type(ex))

pass

Confidence interval for xi = [-0.334109, -0.0802265]

Return level estimate from the estimated stationary GEV

We estimate the -block return level

: it is computed as a particular quantile of the

GEV model estimated using the log-likelihood function. We just have to use the maximum log-likelihood

estimator built in the previous section.

As the data are annual sea-levels, each block corresponds to one year: the 10-year return level

corresponds to and the 100-year return level corresponds to

.

The method provides the asymptotic distribution of the estimator

which mean is the return-level estimate.

zm_10 = factory.buildReturnLevelEstimator(result_LL, 10.0)

return_level_10 = zm_10.getMean()

print("Maximum log-likelihood function : ")

print(f"10-year return level = {return_level_10}")

return_level_ci10 = zm_10.computeBilateralConfidenceInterval(0.95)

print(f"CI = {return_level_ci10}")

Maximum log-likelihood function :

10-year return level = [1.73376]

CI = [1.68892, 1.7786]

zm_100 = factory.buildReturnLevelEstimator(result_LL, 100.0)

return_level_100 = zm_100.getMean()

print(f"100-year return level = {return_level_100}")

return_level_ci100 = zm_100.computeBilateralConfidenceInterval(0.95)

print(f"CI = {return_level_ci100}")

100-year return level = [1.89328]

CI = [1.79336, 1.99319]

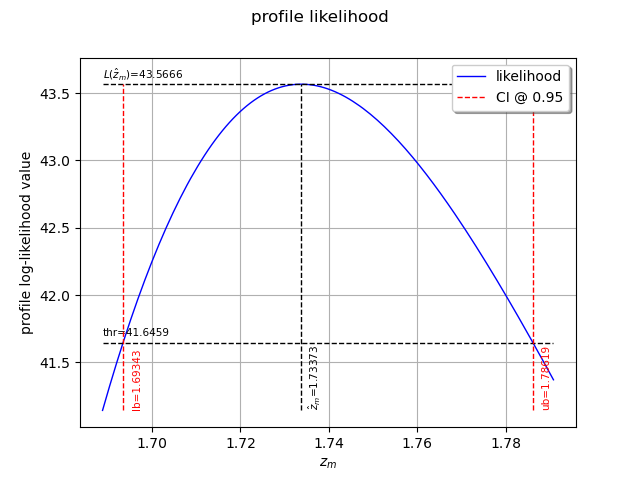

Return level estimate via the profile log-likelihood function of a stationary GEV

We can estimate the -block return level

directly from the data using the profile

likelihood with respect to

.

result_zm_10_PLL = factory.buildReturnLevelProfileLikelihoodEstimator(sample, 10.0)

zm_10_PLL = result_zm_10_PLL.getParameter()

print(f"10-year return level (profile) = {zm_10_PLL}")

10-year return level (profile) = 1.7337304564424916

We can get the confidence interval of : once more, it appears to be a bit smaller

than the interval obtained from the log-likelihood function.

As for the confidence interval of

, depending on the order requested, the interval might

not be calculated.

result_zm_10_PLL.setConfidenceLevel(0.95)

try:

return_level_ci10 = result_zm_10_PLL.getParameterConfidenceInterval()

except Exception as ex:

print(type(ex))

pass

print("Maximum profile log-likelihood function : ")

print(f"CI={return_level_ci10}")

Maximum profile log-likelihood function :

CI=[1.69343, 1.78619]

We can also plot the profile log-likelihood function and get the confidence interval, the optimal value

of and its confidence interval.

view = otv.View(result_zm_10_PLL.drawProfileLikelihoodFunction())

Non stationary GEV modeling via the log-likelihood function

If we look at the data carefully, we see that the pattern of variation has not remained constant over the observation period. There is an increase in the data through time. We want to model this dependence because a slight increase in extreme sea-levels might have a significant impact on the safety of coastal flood defenses.

We have define the functional basis for each parameter of the GEV model. Even if we have

the possibility to affect a time-varying model to each of the 3 parameters ,

it is strongly recommended not to vary the parameter

and to let it constant.

For numerical reasons, it is strongly recommended to normalize all the data as follows:

where:

the CenterReduce method where

is the mean time stamps and

is the standard deviation of the time stamps;

the MinMax method where

is the initial time and

the final time;

the None method where

and

: in that case, data are not normalized.

We suppose that is linear in time, and that the other parameters remain constant:

constant = ot.SymbolicFunction(["t"], ["1.0"])

basis = ot.Basis([constant, ot.SymbolicFunction(["t"], ["t"])])

# basis for mu, sigma, xi

muIndices = [0, 1] # linear

sigmaIndices = [0] # stationary

xiIndices = [0] # stationary

timeStamps = data[:, 0]

We can now estimate the list of coefficients

using the log-likelihood of the data.

We test the 3 normalizing methods and both initial points in order to evaluate their impact on the results. We can see that:

both normalization methods lead to the same result for

,

and

(note that

depends on the normalization function),

both initial points lead to the same result when the data have been normalized,

it is very important to normalize all the data: if not, the result strongly depends on the initial point and it differs from the result obtained with normalized data. The results are not optimal in that case since the associated log-likelihood are much smaller than those obtained with normalized data.

print("Linear mu(t) model:")

for normMeth in ["MinMax", "CenterReduce", "None"]:

for initPoint in ["Gumbel", "Static"]:

print(f"normMeth = {normMeth}, initPoint = {initPoint}")

# The ot.Function() is the identity function.

result = factory.buildTimeVarying(

sample,

timeStamps,

basis,

muIndices,

sigmaIndices,

xiIndices,

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

initPoint,

normMeth,

)

beta = result.getOptimalParameter()

print(f"beta = {beta}")

print(f"Max log-likelihood = {result.getLogLikelihood()}")

Linear mu(t) model:

normMeth = MinMax, initPoint = Gumbel

beta = [1.3821,0.187126,0.124302,-0.124882]

Max log-likelihood = 49.912792759600805

normMeth = MinMax, initPoint = Static

beta = [1.38227,0.186899,0.124343,-0.125475]

Max log-likelihood = 49.91281020707175

normMeth = CenterReduce, initPoint = Gumbel

beta = [1.48016,0.0541552,0.124306,-0.124888]

Max log-likelihood = 49.91279529325528

normMeth = CenterReduce, initPoint = Static

beta = [1.48022,0.0541103,0.124358,-0.125708]

Max log-likelihood = 49.912796771958874

normMeth = None, initPoint = Gumbel

beta = [1.47155,1.67803e-05,0.211226,0.0876902]

Max log-likelihood = 26.490076768443522

normMeth = None, initPoint = Static

beta = [1.4823,1.34614e-09,0.141241,-0.217051]

Max log-likelihood = 43.566619143025775

According to the previous results, we choose the MinMax normalization method and the Gumbel initial point. This initial point is cheaper than the Static one as it requires no optimization computation.

result_NonStatLL = factory.buildTimeVarying(

sample,

timeStamps,

basis,

muIndices,

sigmaIndices,

xiIndices,

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

"Gumbel",

"MinMax",

)

beta = result_NonStatLL.getOptimalParameter()

print(f"beta = {beta}")

print(f"mu(t) = {beta[0]:.4f} + {beta[1]:.4f} * tau(t)")

print(f"sigma = {beta[2]:.4f}")

print(f"xi = {beta[3]:.4f}")

beta = [1.3821,0.187126,0.124302,-0.124882]

mu(t) = 1.3821 + 0.1871 * tau(t)

sigma = 0.1243

xi = -0.1249

You can get the expression of the normalizing function :

normFunc = result_NonStatLL.getNormalizationFunction()

print("Function tau(t): ", normFunc)

print("c = ", normFunc.getEvaluation().getImplementation().getCenter()[0])

print("1/d = ", normFunc.getEvaluation().getImplementation().getLinear()[0, 0])

Function tau(t): class=LinearFunction name=Unnamed implementation=class=LinearEvaluation name=Unnamed center=[1897] constant=[0] linear=[[ 0.0108696 ]]

c = 1897.0

1/d = 0.010869565217391304

You can get the function where

.

functionTheta = result_NonStatLL.getParameterFunction()

We get the asymptotic distribution of to compute some confidence intervals of

the estimates, for example of order

.

dist_beta = result_NonStatLL.getParameterDistribution()

confidence_level = 0.95

for i in range(beta.getSize()):

lower_bound = dist_beta.getMarginal(i).computeQuantile((1 - confidence_level) / 2)[

0

]

upper_bound = dist_beta.getMarginal(i).computeQuantile((1 + confidence_level) / 2)[

0

]

print(

"Conf interval for beta_"

+ str(i + 1)

+ " = ["

+ str(lower_bound)

+ "; "

+ str(upper_bound)

+ "]"

)

Conf interval for beta_1 = [1.3760619004522263; 1.3881370574735519]

Conf interval for beta_2 = [0.17703896126886012; 0.19721356765581052]

Conf interval for beta_3 = [0.12188407872826672; 0.1267190556645434]

Conf interval for beta_4 = [-0.142994007106013; -0.10677058768572634]

In order to compare different modelings, we get the optimal log-likelihood of the data for both stationary and non stationary models. The difference is significant enough to be in favor of the non stationary model.

print("Max log-likelihood: ")

print("Stationary model = ", result_LL.getLogLikelihood())

print("Non stationary linear mu(t) model = ", result_NonStatLL.getLogLikelihood())

Max log-likelihood:

Stationary model = 43.566611777651026

Non stationary linear mu(t) model = 49.912792759600805

In order to draw some diagnostic plots similar to those drawn in the stationary case, we refer to the

following result: if is a non stationary GEV model parametrized by

,

then the standardized variables

defined by:

have the standard Gumbel distribution which is the GEV model with .

As a result, we can validate the inference result thanks the 4 usual diagnostic plots:

the probability-probability pot,

the quantile-quantile pot,

the return level plot,

the data histogram and the density of the fitted model.

using the transformed data compared to the Gumbel model. We can see that the adequation is better than with the stationary model.

graph = result_NonStatLL.drawDiagnosticPlot()

view = otv.View(graph)

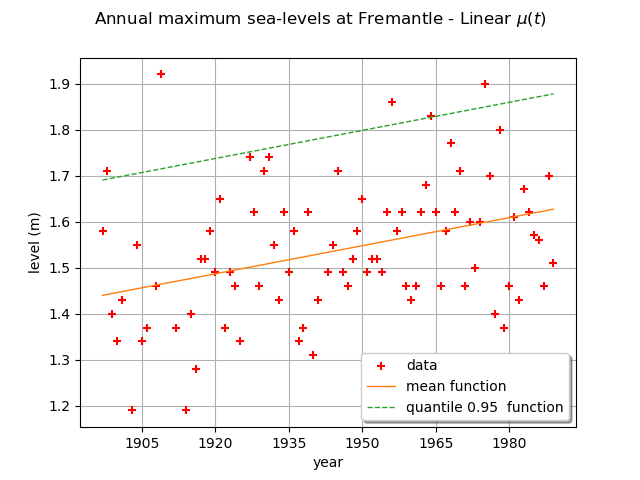

We can draw the mean function . Be careful, it is not the function

. As a matter of fact, the mean is defined for

only and in that case,

for

, we have:

and for , we have:

where is the Euler constant.

We can also draw the function where

is the quantile of

order

of the GEV distribution at time

.

Here,

is a linear function and the other parameters are constant, so the mean and the quantile

functions are also linear functions.

graph = ot.Graph(

r"Annual maximum sea-levels at Fremantle - Linear $\mu(t)$",

"year",

"level (m)",

True,

"",

)

graph.setIntegerXTick(True)

# data

cloud = ot.Cloud(data[:, :2])

cloud.setColor("red")

graph.add(cloud)

# mean function

meandata = [

result_NonStatLL.getDistribution(t).getMean()[0] for t in data[:, 0].asPoint()

]

curve_meanPoints = ot.Curve(data[:, 0].asPoint(), meandata)

graph.add(curve_meanPoints)

# quantile function

graphQuantile = result_NonStatLL.drawQuantileFunction(0.95)

drawQuant = graphQuantile.getDrawable(0)

drawQuant = graphQuantile.getDrawable(0)

drawQuant.setLineStyle("dashed")

graph.add(drawQuant)

graph.setLegends(["data", "mean function", "quantile 0.95 function"])

graph.setLegendPosition("lower right")

view = otv.View(graph)

At last, we can test the validity of the stationary model

relative to the model with time varying parameters

. The

model

is parametrized by

and the model

is parametrized by

: so we have

.

We use the Likelihood Ratio test. The null hypothesis is the stationary model .

The Type I error

is taken equal to 0.05.

This test confirms that the dependence through time is not negligible: it means that the linear

component explains a large variation in the data.

llh_LL = result_LL.getLogLikelihood()

llh_NonStatLL = result_NonStatLL.getLogLikelihood()

modelM0_Nb_param = 3

modelM1_Nb_param = 4

resultLikRatioTest = ot.HypothesisTest.LikelihoodRatioTest(

modelM0_Nb_param, llh_LL, modelM1_Nb_param, llh_NonStatLL, 0.05

)

accepted = resultLikRatioTest.getBinaryQualityMeasure()

print(

f"Hypothesis H0 (stationary model) vs H1 (linear mu(t) model): accepted ? = {accepted}"

)

Hypothesis H0 (stationary model) vs H1 (linear mu(t) model): accepted ? = False

We detail the statistics of the Likelihood Ratio test: the deviance statistics follows

a

distribution.

The model

is rejected if the deviance statistics estimated on the data is greater than

the threshold

or if the p-value is less than the Type I error

.

print(f"Dp={resultLikRatioTest.getStatistic():.2f}")

print(f"alpha={resultLikRatioTest.getThreshold():.2f}")

print(f"p-value={resultLikRatioTest.getPValue():.2f}")

Dp=12.69

alpha=0.05

p-value=0.00

We can perform the same study with a quadratic model for or a linear model for

and

:

or

For each model, we give the log-likelihood values and we test the validity of each model with respect

to the non stationary model where is linear.

We notice that there is no evidence to adopt a quadratic model for

nor a linear model

for

and

: the optimal log-likelihood for each model is very near the likelihood

we obtained with a linear model for

only. It means that these both models do not bring significant

improvements with respect to model tested before.

basis = ot.Basis(

[constant, ot.SymbolicFunction(["t"], ["t"]), ot.SymbolicFunction(["t"], ["t^2"])]

)

result_NonStatLL_2 = factory.buildTimeVarying(

sample,

timeStamps,

basis,

[0, 1, 2],

[0],

[0],

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

"Gumbel",

"MinMax",

)

result_NonStatLL_3 = factory.buildTimeVarying(

sample,

timeStamps,

basis,

[0, 1],

[0, 1],

[0],

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

ot.Function(),

"Gumbel",

"MinMax",

)

print("Max log-likelihood = ")

print("Non stationary quadratic mu(t) model = ", result_NonStatLL_2.getLogLikelihood())

print(

"Non stationary linear mu(t) and sigma(t) model = ",

result_NonStatLL_3.getLogLikelihood(),

)

llh_LL = result_LL.getLogLikelihood()

llh_NonStatLL_2 = result_NonStatLL_2.getLogLikelihood()

llh_NonStatLL_3 = result_NonStatLL_3.getLogLikelihood()

resultLikRatioTest_2 = ot.HypothesisTest.LikelihoodRatioTest(

4, llh_NonStatLL, 5, llh_NonStatLL_2, 0.05

)

resultLikRatioTest_3 = ot.HypothesisTest.LikelihoodRatioTest(

4, llh_NonStatLL, 5, llh_NonStatLL_3, 0.05

)

accepted_2 = resultLikRatioTest_2.getBinaryQualityMeasure()

accepted_3 = resultLikRatioTest_3.getBinaryQualityMeasure()

print(

f"Hypothesis H0 (linear mu(t) model) vs H1 (quadratic mu(t) model): accepted ? = {accepted_2}"

)

print(

f"Hypothesis H0 (linear mu(t) model) vs H1 (linear mu(t) and sigma(t) model): accepted ? = {accepted_3}"

)

Max log-likelihood =

Non stationary quadratic mu(t) model = 50.654392295132084

Non stationary linear mu(t) and sigma(t) model = 50.703072460849185

Hypothesis H0 (linear mu(t) model) vs H1 (quadratic mu(t) model): accepted ? = True

Hypothesis H0 (linear mu(t) model) vs H1 (linear mu(t) and sigma(t) model): accepted ? = True

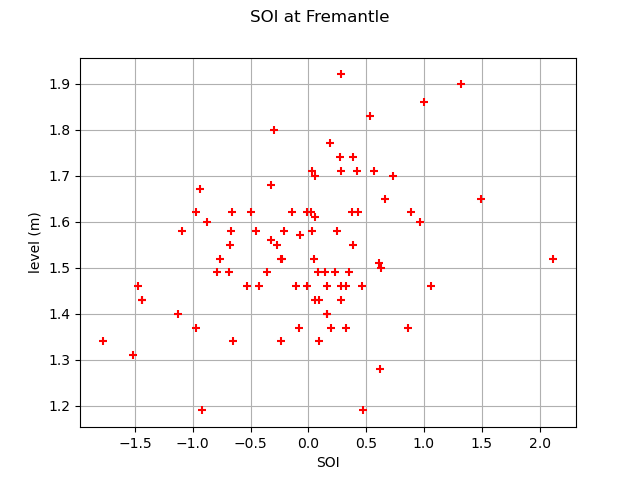

Non stationary GEV modeling with the covariates Time and SOI

Extreme sea-levels can be unusually extreme during periods when the El Nino effect is active. Hence, we study a modeling that takes into account the dependence between the extreme sea-levels at Fremantle and the annual mean value of the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) besides the temporal dependence. The following figure shows that the annual maximum sea-levels are generally greater when the value of SOI is high. It might be due to the time trend in the data for the sea-levels and the SOI (each one increases with time). But it can also be possible that the SOI explains some of the variation in annual maximum sea-levels after allowance for the time variation in the process.

graph = ot.Graph("SOI at Fremantle", "SOI", "level (m)", True, "")

cloud = ot.Cloud(data.getMarginal([2, 1]))

cloud.setColor("red")

graph.add(cloud)

view = otv.View(graph)

To consider this possibility, we study the model:

We consider two covariates: the time and the SOI. We build the sample of the values of both

covariates: where

.

The constant covariate is

automatically added by the library if not specified in order to allow

some of the GEV parameters to remain constant (ie independent of both covariates

):

this is the case for the

and

parameters.

This last constant covariate is associated to the

third component of the covariates sample which now gathers the values

for

.

dataCovariates = data.getMarginal([0, 2])

print(dataCovariates[0:10])

result_Cov = factory.buildCovariates(sample, dataCovariates, [0, 1])

[ Year SOI ]

0 : [ 1897 -0.67 ]

1 : [ 1898 0.57 ]

2 : [ 1899 0.16 ]

3 : [ 1900 -0.65 ]

4 : [ 1901 0.06 ]

5 : [ 1903 0.47 ]

6 : [ 1904 0.39 ]

7 : [ 1905 -1.78 ]

8 : [ 1906 0.2 ]

9 : [ 1908 0.28 ]

We check here that a third component has effectively been added to the covariates sample: see the added third column which is constant equal to 1.

print(result_Cov.getCovariates()[0:10])

[ Year SOI v0 ]

0 : [ 1897 -0.67 1 ]

1 : [ 1898 0.57 1 ]

2 : [ 1899 0.16 1 ]

3 : [ 1900 -0.65 1 ]

4 : [ 1901 0.06 1 ]

5 : [ 1903 0.47 1 ]

6 : [ 1904 0.39 1 ]

7 : [ 1905 -1.78 1 ]

8 : [ 1906 0.2 1 ]

9 : [ 1908 0.28 1 ]

We get the optimal parameter .

beta = result_Cov.getOptimalParameter()

print("beta = ", beta)

beta = [0.00211399,0.0543691,-2.62594,0.12072,-0.149739]

We get here the function where

. We see that

depends on the three

covariates

and that

and

depends

only on the third one

which is the constant one.

print(result_Cov.getParameterFunction())

print(f"beta = {beta}")

print(f"mu(t) = {beta[0]:.4f} *t + {beta[1]:.4f} * SOI(t) + {beta[2]:.4f}")

print(f"sigma = {beta[3]:.4f}")

print(f"xi = {beta[4]:.4f}")

ParametricEvaluation([muBeta0,muBeta1,muBeta2,sigmaBeta0,xiBeta0,y0,y1,y2]->[muBeta0 * y0 + muBeta1 * y1 + muBeta2 * y2,sigmaBeta0 * y2,xiBeta0 * y2], parameters positions=[0,1,2,3,4], parameters=[muBeta0 : 0.00211399, muBeta1 : 0.0543691, muBeta2 : -2.62594, sigmaBeta0 : 0.12072, xiBeta0 : -0.149739], input positions=[5,6,7])

beta = [0.00211399,0.0543691,-2.62594,0.12072,-0.149739]

mu(t) = 0.0021 *t + 0.0544 * SOI(t) + -2.6259

sigma = 0.1207

xi = -0.1497

We check here the normalizing function that has been used, which comes from the default method (the MinMax one).

print(result_Cov.getNormalizationFunction())

class=LinearFunction name=Unnamed implementation=class=LinearEvaluation name=Unnamed center=[1897,-1.78,0] constant=[0,0,0] linear=[[ 0.0108696 0 0 ]

[ 0 0.25641 0 ]

[ 0 0 1 ]]

We test this new model where is modeled as a linear combination

of the three covariates

against the model

with the linear-trend only

. The maximized log-likelihood of this

new model is 53.9, compared to 49.9 for the first model. Hence, the

deviance statistics is equal to

, which is large when judged relative to

a

distribution.

It provides evidence that the effect of SOI is influential on annual maximum

sea-levels at Fremantle, even after the allowance for time-variation.

llh_cov = result_Cov.getLogLikelihood()

print("Max log-likelihood: ", llh_cov)

resultLikRatioTest_SOI = ot.HypothesisTest.LikelihoodRatioTest(

4, llh_NonStatLL, 5, llh_cov, 0.05

)

print(f"Dp={resultLikRatioTest_SOI.getStatistic():.2f}")

accepted = resultLikRatioTest_SOI.getBinaryQualityMeasure()

print(

f"Hypothesis H0 (linear-trend mu(t) model) vs H1 (linear-trend and SOI mu(t,SOI) model): accepted ? = {accepted}"

)

Max log-likelihood: 53.89871913089317

Dp=7.97

Hypothesis H0 (linear-trend mu(t) model) vs H1 (linear-trend and SOI mu(t,SOI) model): accepted ? = False

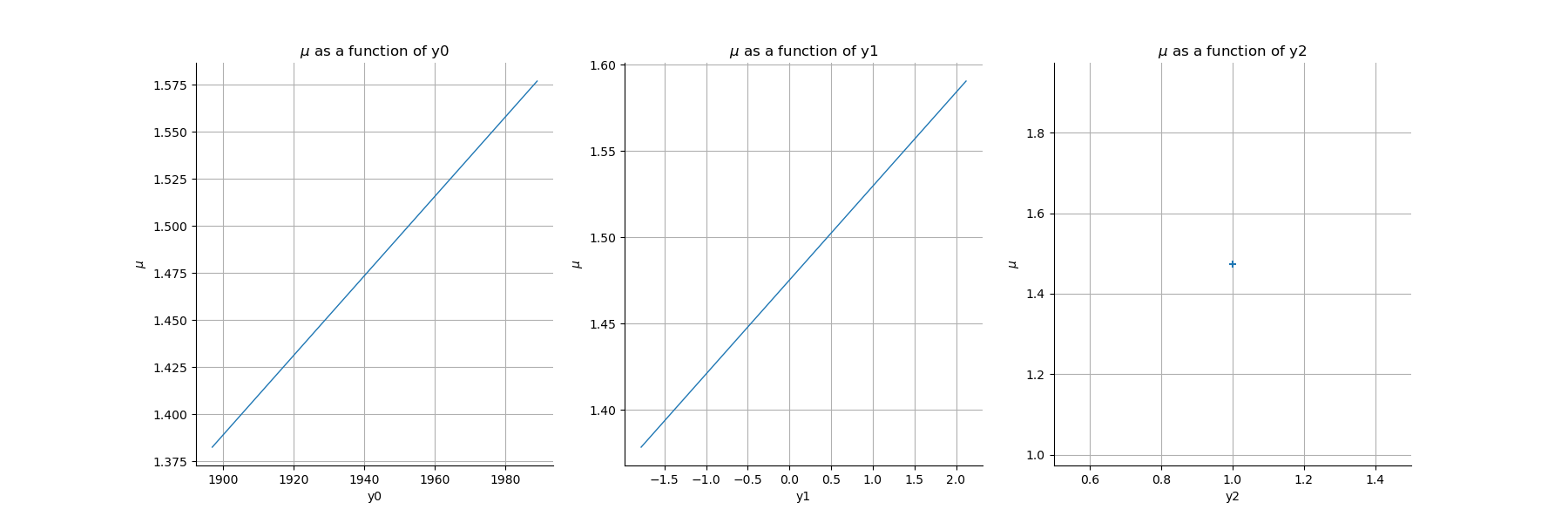

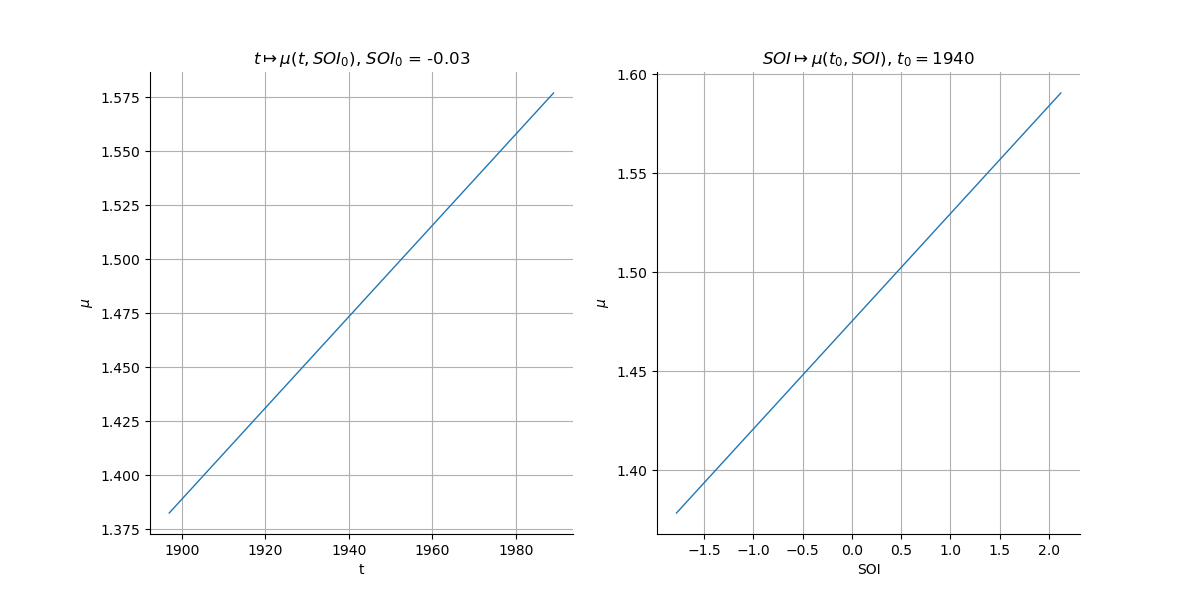

We plot here the graphs where

is a given value (the mean value of the sample if not specified),

and

where

is a given time.

Care: there are three covariates

for the reasons mentioned previously.

Then the reference point must be of dimension 3.

As the relation is linear (the link function is the Identity function), we get some straight lines. The third graph is the dependence on the third covariate which is constant.

refSOI = dataCovariates.computeMean()[1]

refTime = 1940

refPoint = [refTime, refSOI, 1]

gridMu = result_Cov.drawParameterFunction1D(0, refPoint)

view = otv.View(gridMu)

To adapt the labels and get rid of the last graph:

graphCol = gridMu.getGraphCollection()

graphMu1 = graphCol[0]

graphMu1.setTitle(r"$t \mapsto \mu(t, SOI_0)$, $SOI_0$ = {0:.2f}".format(refSOI))

graphMu1.setXTitle("t")

graphMu2 = graphCol[1]

graphMu2.setTitle(r"$SOI \mapsto \mu(t_0, SOI)$, $t_0 = $" + str(refTime))

graphMu2.setXTitle("SOI")

newGridLayout = ot.GridLayout(1, 2)

newGridLayout.setGraph(0, 0, graphMu1)

newGridLayout.setGraph(0, 1, graphMu2)

view = otv.View(newGridLayout)

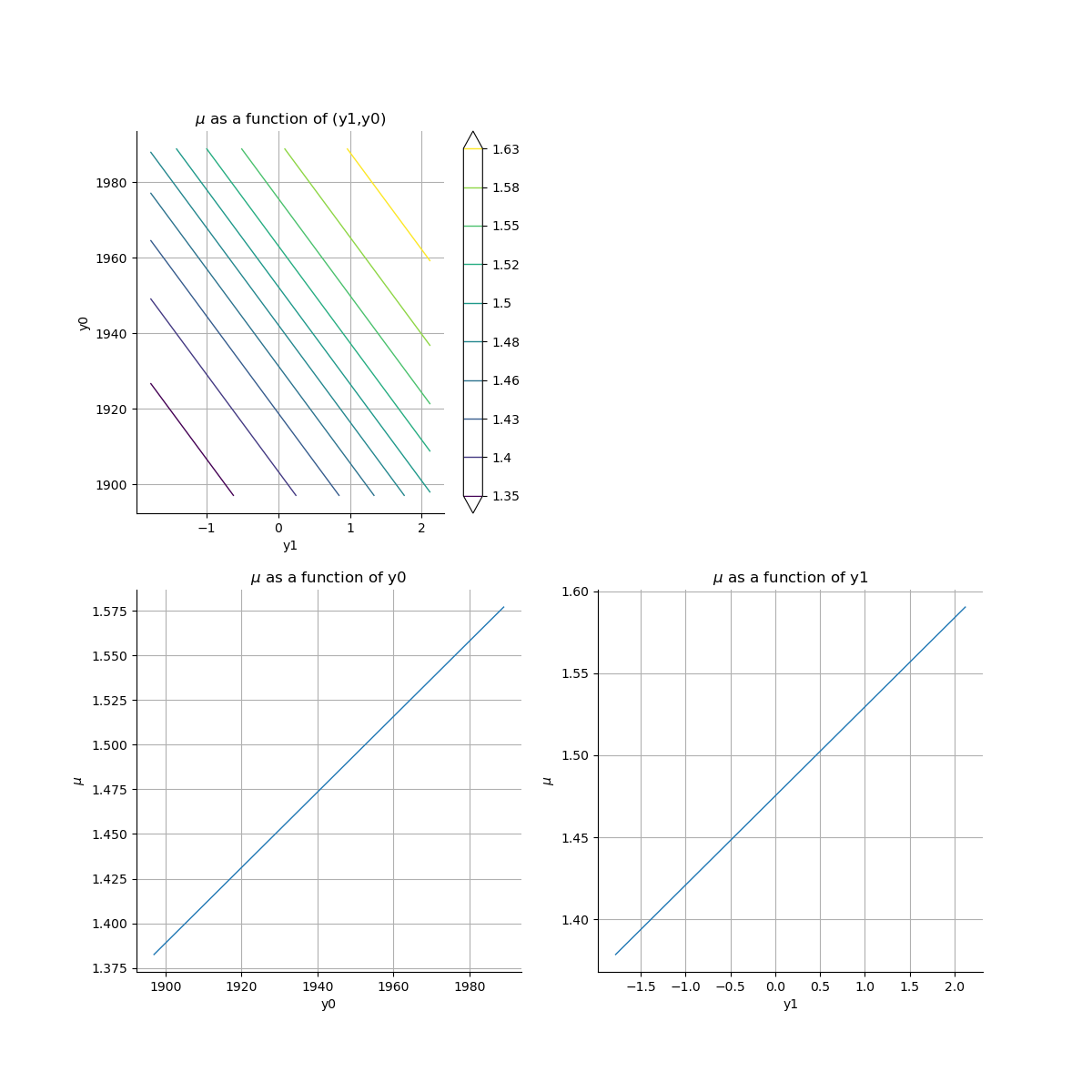

We plot here the graph .

As the third covariate is constant, the other graphs

and

are not interesting

as we have already obtained them with the previous method.

graphCol = result_Cov.drawParameterFunction2D(0, refPoint)

view = otv.View(graphCol)

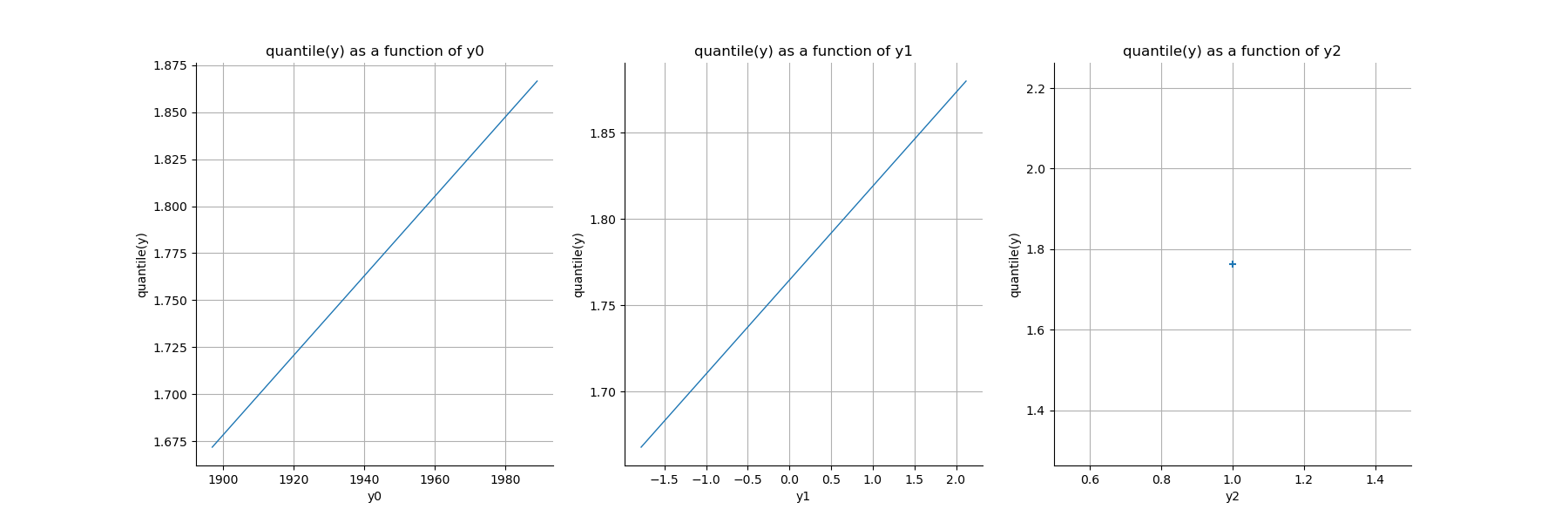

We plot here the graphs

and

where

is the process whose excesses of

follow the estimated GPD,

depending on the covariates

. Then

is the quantile of order

.

Because of the constant third covariate, the last graph is reduced to a point.

p = 0.95

gridQuantile = result_Cov.drawQuantileFunction1D(p, refPoint)

view = otv.View(gridQuantile)

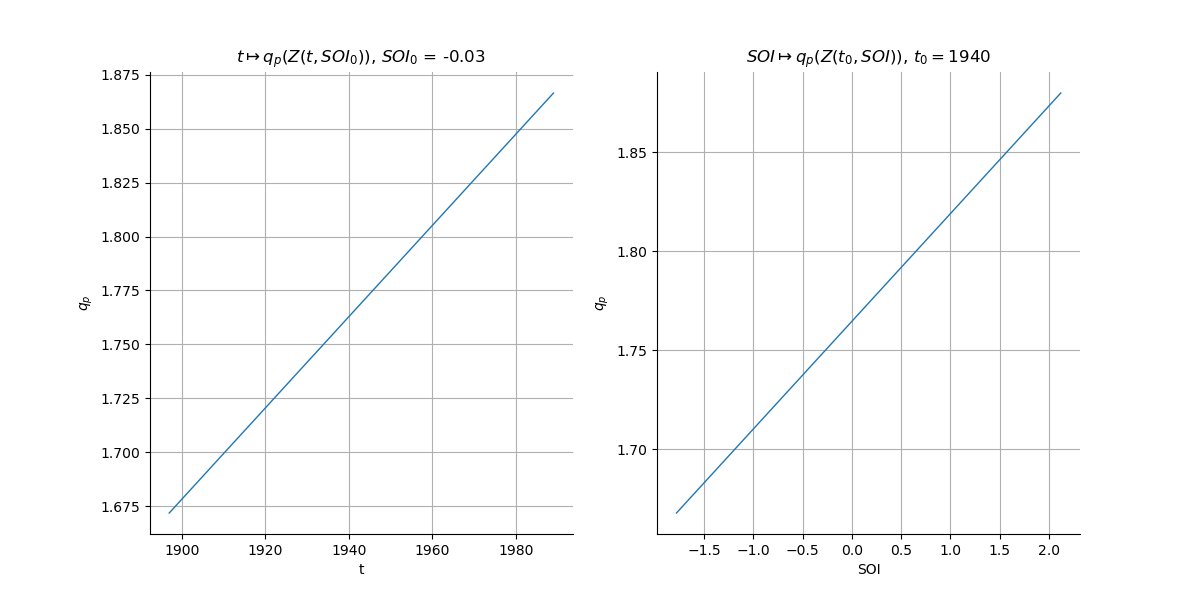

To adapt the labels and get rid of the last graph:

graphCol = gridQuantile.getGraphCollection()

graphQuant1 = graphCol[0]

graphQuant1.setTitle(r"$t \mapsto q_p(Z(t, SOI_0))$, $SOI_0$ = {0:.2f}".format(refSOI))

graphQuant1.setXTitle("t")

graphQuant1.setYTitle(r"$q_p$")

graphQuant2 = graphCol[1]

graphQuant2.setTitle(r"$SOI \mapsto q_p(Z(t_0, SOI))$, $t_0 = $" + str(refTime))

graphQuant2.setXTitle("SOI")

graphQuant2.setYTitle(r"$q_p$")

newGridLayout = ot.GridLayout(1, 2)

newGridLayout.setGraph(0, 0, graphQuant1)

newGridLayout.setGraph(0, 1, graphQuant2)

view = otv.View(newGridLayout)

otv.View.ShowAll()

Total running time of the script: (0 minutes 3.540 seconds)

OpenTURNS

OpenTURNS